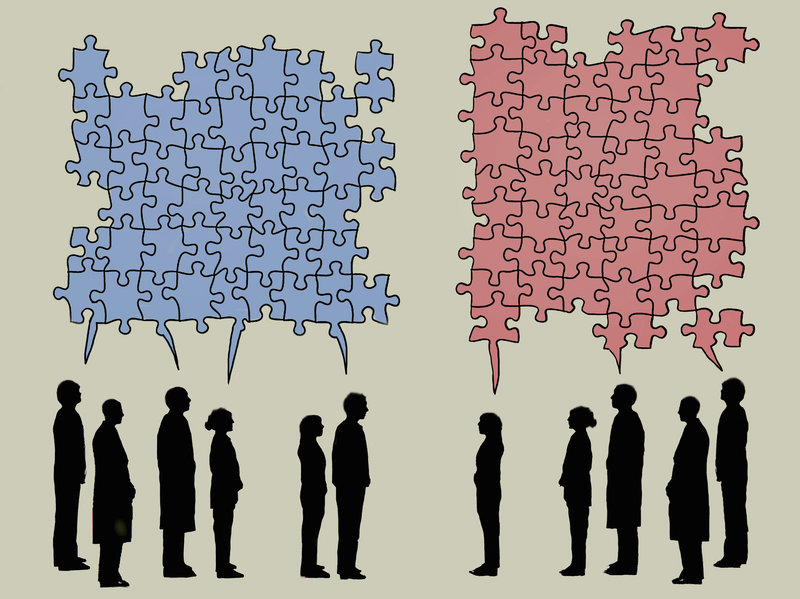

You have probably never wondered what African-American women have in common with Professor Richard Dawkins. I would not blame you. The comparison seems like one of chalk to cheese. Be that as it may, they have more in common with the brilliant professor than you could ever guess on any cursory observation. On the western side of the Atlantic, African-American women remain loyal to black men and to the black struggle. They continue to sacrifice themselves to maintain relationships which do not serve them, despite statistics which suggest that they should do the opposite. On the eastern side of the pond, the British DNA nerd has inadvertently made himself the sacrificial lamb at the progressive altar in an effort to maintain social and political capital. The cost to both African-American women and to Dawkins is their dignity, but it seems that this matters not. Humans are, of course, a tribal bunch. Tribalism is in our DNA as a social species and makes us love those similar to us more than others… as we should. Things go awry, however, when this innate tribalism affects our higher cognitive processes.

In Dawkins’ case, he asked a “dangerous” question on Twitter:

“In 2015, Rachel Dolezal, a white chapter president of NAACP, was vilified for identifying as Black. Some men choose to identify as women, and some women choose to identify as men. You will be vilified if you deny that they literally are what they identify as. Discuss.”

If both race and gender are social constructs as people in the postmodernist camp generally suggest, then any challenge to Dolezal’s assertion, like with transgender people, must stop at her subjective identification. It was a reasonable comparison of the two issues in my view, but reasonable comparisons seldom survive the onslaught of the Twitterati.

Tweet after tweet called for the prominent humanist’s head. Public atheists Matt Dillahunty and Hemant Mehta joined in the chant of “Transphobe! Transphobe! Transphobe!” eager to castigate the man for his alleged treachery. His transgression, they suggested, was to forsake science for bigotry. The flagellation continued for days and rumour has it Dawkins prayed.

Of course there were sensible voices in the crowd pleading for reason over the treason charge, but it was then that the kick from Dawkins came. He tweeted:

“I do not intend to disparage trans people. I see that my academic “Discuss” question has been misconstrued as such and I deplore this. It was also not my intent to ally in any way with Republican bigots in US now exploiting this issue.”

OUCH!

In The Square and the Tower: Networks, Hierarchies and the Struggle for Global Power, Hoover Institute Fellow and history Professor Niall Ferguson describes how communication technologies like the printing press, the internet and modern day social media are polarizing. According to Ferguson, they exacerbate our tribalism, whatever form that they take on in a given era, and are as effective (if not more effective) at spreading both harmful and helpful ideas. When they are utilized, people tend to divide themselves into echo chambers. Twitter is but one polarizing force, and anyone who has been on the platform long enough knows that you never, under any circumstance, EVER cave to the mob. It is social suicide. Nothing good comes of it, and it is pointless because apologies are worth nothing in the Twitterverse. To cave to the mob while simultaneously alienating the people who are defending your right to ask a question though? That is just pure gold!

In his book Against Empathy: A Case For Rational Compassion, Yale Professor of Psychology Paul Bloom proffers that empathy is sometimes useful, but not the ideal that we typically make it out to be. He argues that since our natural, knee-jerk empathy is more strongly felt for people we perceive as closer to ourselves, whether biologically or socially, it limits our capacity to give due attention to people and issues which are worthy of regard, but with which we cannot relate. Bloom highlights that empathy’s limitations can cloud our judgment and even cause us to do evil.

It is counterintuitive to think that it was empathy that made Dawkins do a Twitter kamikaze, but as complicated as it seems, it was exactly that dark, tribalistic side of empathy at play in this debacle. For decades, Dawkins has presented himself as the secular, liberal voice of reason, science and all things modern. His desire to maintain that reputation and his failure to keep his finger on the social pulse, however, caused him to err. Just as religion does not and cannot have a monopoly on morality, those who label themselves as progressive liberals do not and cannot monopolize reasonableness. Much of the censorship of valid, public discussion –the main thing Dawkins cherishes– has been championed by people whom he would not readily attach a label of “bigots” to, despite them being just that. Conversely, a lot of the time, it is those “Republican bigots” (and I hate the label just if that has not become obvious) who defend freedom of speech and of inquiry. This is not meant to absolve actual right-wing bigots from their bad behaviour. They can do deplorable things, much like other groups. When that happens, it is the responsibility of the reasonable masses to challenge them.

But it is not only “Republican bigots” who question the postmodernist construction ideology that transgenderism falls squarely within. It is not a tribal issue but a scientific one. What was required in the circumstance was loyalty, not to labels, but to ideas and principles. Had Dawkins remembered that, he would have been able to see the humanity in the “Republican bigots” he so quickly threw under the bus. A fruitful discussion could have been had as he originally intended, and this would have kept his reputation for non-partisan debate in tact as well.

Instead, he chose his desire to remain in the good books of progressive pundits by trying to straddle the fence. His intended clarification of his tweets did not sit well with many of the non-progressives who started off in his army, and that chink in his armor cost him his 1996 Humanist of the Year award from the American Humanist Association. It isn’t that the nonsensical revocation does much to his record, but that the idea that tribal labels and loyalty to them can be counterproductive still resonates. Sometimes, our ideas will have us associated with people whom we do not usually agree with, and that is okay.

For African-American women, the tale is much more grim.

In his book Is Marriage For White People?: How the African-American Marriage Decline Affects Everyone, Stanford Law Professor Ralph Richard Banks discusses the low marriage rates among African Americans and analyzes the reasons for them. Of note were African-American women’s loyalty to the “cultural swagger” of black men, and their hesitancy to interracially date and marry, which were described as inimical to their intimate relationship success. One has to look no further than this Brookings Institute paper to understand the problem and what has to be done, but at the risk of being pedantic, I will spell it out plainly below.

Heterosexual women are picky in mating because pregnancy is more of a biological risk and investment for women than it is for men. They marry men three to five years older than them on average, and also tend towards hypergamy, marrying across and up competence and dominance hierarchies. This is the typical human mating strategy, but there is nothing typical about the African-American community’s condition.

With high rates of incarceration, violent death and school dropout among young African-American men, their female counterparts outnumber and outperform them exponentially. If this was the case for men in general, it would cause a reversal in the human sexual dynamic. The paucity of high quality men would result in fiercer competition among women for the men at the top of the hierarchy. Is this the case among African-Americans? Absolutely!

The angry baby mama trope exists for a reason, and as Banks notes, the few black men who do succeed educationally and socioeconomically marry interracially at three times the rate as black women… if they even marry at all. Most do not marry because business is booming! They get sex, children, companionship and places to rest their heads, without having to invest anywhere near as much as African-American women do. It is the typical “Why by the cow when you can get the milk for free?” dynamic and it pays them in dividends.

Banks’ solution, of course, is that African-American women should publicly and seriously consider interracial relationships. Their choice to do this would reintroduce a more typical sexual dynamic, since there would be more men competing for their affections when word gets out about their openness. This would mean more opportunities for them to exercise their own sexual selectivity. It is common sense. It is math.

Like Dawkins did to the “Republicans” supporting him, however, swathes of African-American women choose to disparage people like Banks and like author Christelyn Karazin, who in her book Swirling: How to Date, Mate and Relate Mixing Race, Color and Creed, advocates for black women to entertain all their romantic options to maximize their relational happiness and success. Karazin has dedicated her professional life to the African-American woman’s plight, creating the No Wedding No Womb project to warn women about the negative consequences of out-of-wedlock maternity. She has even created a course, The Pink Pill, to help the lot strategize, through self-development, so that they could become more equipped to navigate newer, more affluent social circles.

What has she gotten in return? They take it as an affront to “blackness” and to the “honour” of the black man. She has been called a bed wench, a race traitor, and all manner of insulting things, while being told that she just wants to be white. The African-American women in whom she has invested all her sweat equity have teamed up with the black men who have them in their predicament and who, online and offline, demonstrate no apprehensions about expressing their obloquy for black women. The alliance is made along cultural and racial lines of course, and it only facilitates their own embarrassment. If these women were brave enough to disengage from their emotional reasoning and look at the statistics instead of shooting the messenger, I am certain that their romantic, social and economic outcomes would shift towards more favourable outcomes, but alas, tribalism!

I suppose I should get to the point of this post after all my chuntering. It is that tribal disloyalty is not an iniquity, but the truest virtue. The idea of rational compassion forwarded by Bloom addresses our altruistic choices, but I think it must be taken further. Generally speaking, it is tribalism which must be deliberately circumvented to maintain healthy social intercourse and secure better social, political and economic outcomes. I therefore propose that the antidote to our innate tribalism is an amalgamation of rational compassion with intentional disloyalty.

This proposal necessitates some clarification. I do not espouse the idea that objectivity is a social construct. In advocating for active disloyalty within the public square, I recognize that I run the risk of suggesting that we should approach problems as if nothing is true or real. That is the opposite of what I am suggesting, since certain ideas do underpin my proposal.

Firstly, I believe that through a process of rigorous inquiry, we can figure out the truth of most matters. That is the rational bit. Secondly, I believe that social engagement with ideas, even if they are bad, is more useful that censorship could ever be. That means that we must be willing to be disloyal to our biases and to those who agree with us, so that we can modify our points of view as necessary. Thirdly and finally, I believe that the human individual is valuable and should be treated with dignity. That is the compassion. Loyalty to these principles and active disloyalty to familiar people and institutions would help to solve the tribalism problem.

If we agree that there are objective truths and that we can decipher them through rigorous inquiry, then it puts us in the mind-frame of addressing the problem rather than the person. We would have a keen awareness that there is a destination which we can eventually reach it if we try hard enough. Depersonalizing the problem and stripping it down to its bare bones for the mutual benefit of edification is what science is all about. Fisher, Ury and Patton suggest that this is the principled approach to problem-solving and promote in their best-selling book on alternative dispute resolution, Getting To Yes.

To adopt a principled approach to problem solving is to be rational. We must be honest about our intentions in debate, must know what our desired outcomes are, must determine whether those outcomes are worth pursuing at any given moment, and must be open to the possibility of outcomes which we may not have originally expected. Importantly, we must divorce our sense of moral worth from the outcome of the inquiry process. If we accept that there are only facts, fictions, and opinions, then developing our skills of distinguishing these items can become our life’s work. This enables us to scrutinize ideas without diminishing people, and to get to the meat of our matters more efficiently.

If we agree that social engagement with ideas is more useful than censorship, then there are no dangerous questions. There are no shadows in which ideological monsters can hide. There are no book burnings and no fatwas and no mobs. There is no Twitterati. It seems idealistic because of our biology, but why would anybody not want to live in a world where his trivial transgressions (real or perceived) do not mean the end of his social life at any given moment? We can affirm not only our ability to pursue truth to its end, as above, but our duty to do so, and that duty becomes one owed not to ourselves or our kin, but to the process. This means that we are all responsible for ourselves, and for keeping each other in check, not through scarlet letters and the mental abuse of isolation, but through rational debate. There can be no loyalty in debate, because it requires us to shine a light on the weaknesses of our own positions.

Finally, if we agree that the individual is valuable and deserves dignity, then we cannot lazily ascribe group traits to him or presume that he embraces all the group’s ideas. We must humanize him and engage with him and him alone. This insures us against the presumption that a perceived opponent malicious, and simultaneously forbids us from assuming that certain people possess virtues and not others without evidence for this presumption. Perfectly reasonable people can disagree with us and unreasonable people can agree with us. Nobody is infallible…not even ourselves. Everybody is human and that sets the tone for our engagement.

It is only when our capabilities, duties and rules of engagement are clear that we can avoid excluding people who have our best interests at heart, but who appear to be from different tribes than ourselves. In one of my favourite plays, Fences by August Wilson, the protagonist Troy and his best friend Bono discuss the purpose of a fence. They conclude that fences are meant to keep people in as much as they are meant to keep people out. While our tribes and our differences define us in many ways, and the lines between us keep us both in and out of each others’ camps, there is no mandate that these are the only ways by which humans can be defined. We are more similar than we are different, and that is why we are all still here on this pale blue dot. In this information age where the tools of everyday life magnify the limitations of our empathy, and where the sociopolitical divisions in the west are pronounced because of the anonymity of screens, we must ensure that our fences do not become walls. Staying loyal to the basic principles outlined herein would mitigate against polarization, help to bridge gaps between people and yield the greatest good for the greatest number of people in the long term.